I’m often asked how I organize the process of gathering requirements, estimating projects, and communicating with clients. A crucial part of this lies in the well-coordinated work of my team, streamlined processes, automation of routine tasks, and of course, the tools and practices I use, which I’ll try to describe here.

First and foremost, when it comes to my approach to project work, it’s important to be able to ask and answer two key questions:

-

What business problem are we solving?

-

What result do we expect as an outcome?

In other words, not “how do we technically send a response to a request,” but rather “what exactly does the business do, what is it betting on, how does it measure success, and how can the system help it grow?” When we stay anchored in this value-driven perspective, it becomes much easier to choose the right technologies, define priorities and tasks, and have meaningful discussions with clients, because clients are primarily interested in solving real business problems.

The true measure of our work’s quality is not the complexity of the technical challenges we overcome, the volume of code written, or the number of features delivered. It’s how much our work helps improve the client’s business and key performance indicators.

As we discuss the project, we begin to build a shared vocabulary that reflects what the business does. This becomes the foundation of the language the entire team will use when talking about the project. Don’t underestimate this step—misunderstandings are common in outsourcing, especially when the client and the team are separated by time zones, age, culture, or language. And the consequences can be dramatic.

Eventually, we clarify what “reporting period,” “expiration date,” “recurring order,” and “value-added tax” mean. Personally, I find it easier to operate with a smaller amount of information than a large one. That’s why mind maps are the ideal tool for me at this stage, they let me group parts of the business domain and focus only on the essentials. (Research shows the brain can hold around seven entities in working memory at once, though that’s individual, I prefer fewer.)

As the project grows, I expand the mind map with new branches, organizing them by domain, business function, team ownership, priority, etc., depending on the project.

For mind mapping, I use the cross-platform, open-source tool FreeMind, which has functionality comparable to commercial alternatives. Some useful features of FreeMind include:

-

The ability to add icon markers to nodes

-

Maps are saved in XML format (not just exported), so you can freely manipulate the data and generate any necessary artifacts

-

The ability to add textual, or more precisely, HTML, descriptions to nodes, which I use as metadata when generating artifacts based on markers

-

The option to add attributes to nodes (e.g., for task estimation), allowing me to calculate overall project estimates

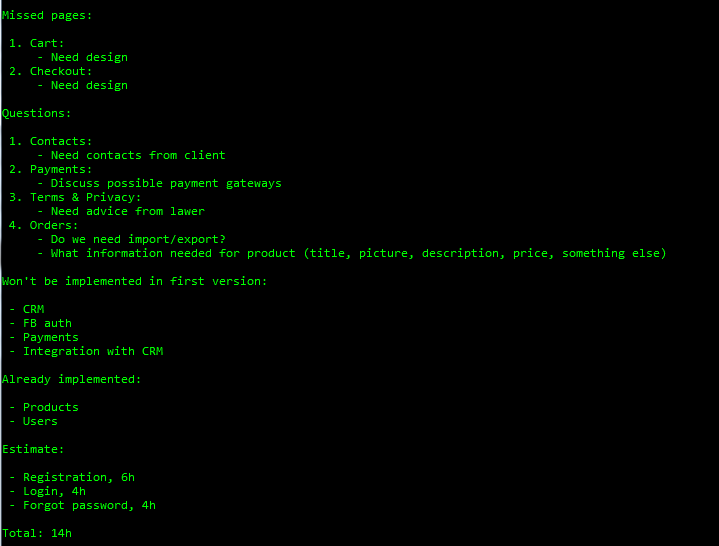

I start building the mind map during the very first project discussions. I mark areas with question marks where details are still unclear and keep them until everything is resolved. I also use icons or notes to indicate what has already been completed, what won’t be done in the current iteration, or what is waiting for design input.

You can find the actual script if you’re interested.

An important principle during the requirements phase is to break down functionality into tasks of no more than 4–8 hours. This helps minimize risk and clarify what exactly needs to be done. If a task is difficult to estimate, it’s likely too vague or too large. In such cases, I either postpone it until the next iteration or continue refining the details. Afterward, I go over everything again with the client to ensure we’re aligned on the process and expected outcomes.

Since we’re an outsourcing company, we handle hundreds of projects across industries like retail, marketing, banking, healthcare, and insurance. A particular challenge arises when working with unfamiliar domains, especially when there’s an intermediary who doesn’t have all the information. My usual approach is to build a concise domain language with the client. Sometimes mathematical notation helps; sometimes something resembling Python works best. Here’s an example of logic written in such a domain-specific language (DSL):

ADD A(100) (transfer_id: 10) DEC A(50) (SOLD by sale_order_id: X) ADD A(50), order_id: X DEC A(10) (SOLD by sale_order_id: Y) ADD A(10), order_id: Y

This kind of clarity, when everyone speaks the same “language,” allows us to compress complex rules into just a few lines, often enough for a documentation page, and greatly simplifies both writing and updating such descriptions.

Since FreeMind saves maps as structured XML, I can store them in version control repositories and track changes almost as easily as with code. I’m a big fan of formats that are readable in any editor, don’t require special software, and work well with version control. That’s why I’ve grown fond of Markdown, Asciidoc, and to a lesser extent, LaTeX.

If you’re working in a high-tech environment where everyone can read code, you might find Jupyter to be a better fit. It’s an open-source platform that lets you write and run code (in Python, Ruby, etc.), document it in Markdown, visualize data, and much more. Here’s an example of what it can look like. Jupyter is a de facto standard in the data science community.